It’s 10:00 a.m. on Saturday, Nov. 11, 2017, and I just finished submitting a few wildlife photos to National Geographic’s “2017 Nature Photographer of the Year Contest.” Several friends of mine suggested I enter after I showed them some of my favorite images from my recent safari to Kenya. I realize it’s a long shot but taking great wildlife photos has more to do with lucky timing than it does mastering the technical aspects of a camera. You have to be willing to endure the process and wait patiently for the opportunity to present itself because you never know when a memorable image will appear in front of your lens.

My brother Justin and I landed on a small airfield inside the Masai Mara National Reserve located in the southwestern corner of Kenya along the border with Tanzania. The 250-mile stretch of savanna was named after the Masai tribe who have inhabited the area for hundreds of years and who once described the area as “Mara,” which means “spotted” in their native language. It’s a landscape dotted with widely-dispersed thorn trees and crop-circled cloud shadows that leave behind patterns similar to those you might see on many of the endangered cats that call the Mara home.

We were picked up from the airstrip in a custom-built Land Rover and driven to an idyllic camp situated on the banks of the Mara River, where a herd of hippos greeted our arrival with thunderous grunts. Security guards, who patrolled the camp day and night, escorted us to our tent and told us to be aware of our surroundings because animals often wandered inside the camp. As an extra layer of protection, guests were not allowed to leave their tents after sundown without an accompanying guard.

We realized why the camp employed so many guards after several Cape buffalo surrounded our tent the first night. Cape buffalo are dangerous animals with curved horns that will make even the fiercest of lions think twice before launching an attack. We could hear them rustling outside of our tent, but we didn’t realize how close they had come until the next morning when we saw their droppings a few feet from our veranda.

It was our first close encounter with one of Africa’s “Big 5” animals and a good preview of what we could expect as we headed out with our driver for our first full day of game viewing. The mornings started out surprisingly cool in the mid-50s but quickly warmed by the afternoon, sometimes climbing as high as the low 90s. At one point, our driver made an unexpected detour and we found ourselves less than 20 feet away from two fully grown male lions. One of the brothers immediately jumped to his feet and studied us suspiciously, while the second lay undisturbed on the ground beside him.

It was an intimidating exchange that proved even more unsettling in an open-aired vehicle with nothing to stop the lions from having their way with us if they felt threatened. It’s the reason why we were required to sign so many waivers when we first arrived at camp. No matter the experience of the staff or the drivers, there’s always the chance that something can go wrong when you’re in close proximity to wild animals.

The Mara landscapes were vast and wide as anything I had ever seen, so much so that six-ton elephants appeared as little specs on the distant horizon. We cruised across the grasslands and eventually caught up with a family of three on an afternoon stroll. The parents fanned their floppy ears and raised their long trunks as we pulled near, while their baby elephant sprayed itself with mud, hoping to beat the heat with an extra layer of sun protection.

We saw three of the “Big 5” animals on our first day—buffalos, lions and elephants—and the following morning provided us our best chance to see the critically endangered black rhinoceros. There are less than 5,000 of this species of rhino left in existence and as few as 30 inside the Mara. To increase our odds at spotting one, we decided to take a hot air balloon ride for an aerial view.

Our pilot had been operating balloons inside the Mara for more than a decade, and he was quick to let us know that there were no guarantees we would see a rhino on our voyage. We hopped into the waiting basket and sailed through the sky just as the sun began to rise across the savanna. Multi-colored balloons dotted the horizon, floating this way and that, rising higher and higher with each fiery blast of their burners.

It was a surreal experience—a mix of serenity and exhilaration—that showcased the true beauty of the Mara. We were at the mercy of the winds, oblivious to the fact that we were on a collision course with something amazing. Hippos bathed in watering holes underneath us, hunting lions chased a pair of desperate wildebeests, and confused elephants blared their trunks in alarm as we passed by. And it wasn’t long before the captain pointed to a pair of rhinos in the distance, their trademark ivory horns jutting from their snouts.

We continued floating overtop a small pocket of trees when, to everyone’s surprise, two more armored bodies bolted out into the open. We ended up seeing not one but four black rhinos during our 45-minute journey, something not even the captain in his 10 years of experience working inside the Mara had ever witnessed on a single trip. As we approached an open clearing, our balloon began its final descent and we prepared for what we knew would be an abrupt landing.

Our basket hit the ground and bounced up and down until finally coming to rest on its side. There was a vehicle waiting to take us to a one-of-a-kind breakfast prepared out in the middle of the open savanna. From there, we headed out for our final drive through the seemingly unending Mara, staring in disbelief at the thousands upon thousands of wildebeests, antelope, and zebra grazing just outside our vehicle.

Wildebeests are a “keystone” species, meaning they play a significant role in the health and well-being of the Mara ecosystem. More than a million of them make the annual migration north from Tanzania’s Serengeti National Park, following the seasonal rains in a giant loop that covers 1,800 square miles. In order to reach the Mara grasslands, however, they first have to first cross crocodile-infested waters.

We drove to a stretch of the Mara River, where crossings were known to occur, just as a new wave of wildebeests were congregating along the edge. The number of wildebeests continued to swell, and more and more vehicles moved into position, each vying for the best view of a wildlife spectacle unlike any other on earth. Our driver parked alongside National Geographic film crews and BBC cameramen, and we all waited patiently for the herd to make its move.

The excitement was palpable even for the skittish animals standing on the water’s edge. They dipped their hooves into the shallow waters and cautiously extended their necks for a drink. But each time we expected them to take the plunge into the murky river, they turned around in fear and headed back the opposite direction. The same scene played at different sections of the river for hours on end as we sat on the edge of our seats underneath the hot African sun.

Unfortunately, we had an early-afternoon plane to catch to Nairobi, so our driver pulled away and headed for camp. We didn’t experience the famed river crossing we had come to see, but the trip definitely didn’t disappoint. The only “Big 5” animal we missed was the elusive and nocturnal leopard, but multiple cheetah sighting proved to be a nice consolation prize. We also saw giraffes, hyenas, warthogs, eagles, vultures, ostriches and even a wild dog.

The moral of the story: the grass may not be greener on the other side of where you're standing, but if wildebeests could talk, they would tell you it sure is greener inside the Mara!

Follow me on Instagram at @Joshua_Maven or @HonchotheVan, on Twitter @MaventheRaven or Facebook at Facebook/TheLastImperial.

Midlife Revival

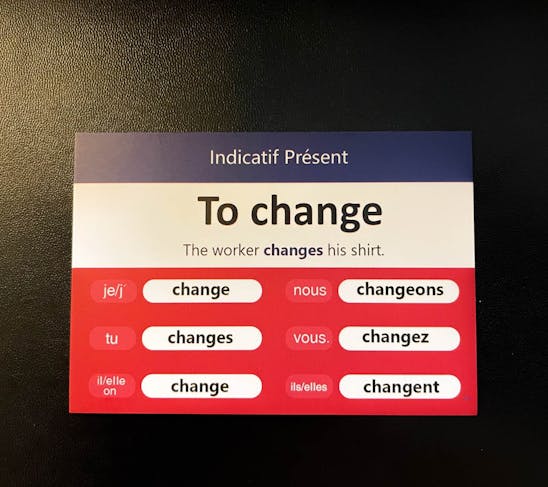

It’s Friday, July 11, 2025, and I just completed my second French lesson of the week. I’ve been working with an online tutor for the past six months in hopes of communicating with my 22-month-old son as he advances in his mother’s native tongue. I’ll be honest, learning a new language has proven quite the challenge. My tutor insists that I’m making progress, but it rarely feels that way to me.

Postcards to Samuel

It's 8:00 p.m. on Wednesday, July 31, 2024, and I'm trying something a little different with this post. Instead of my usual blog format, I compiled a series of postcards that I wrote to my 10-month-old son, Samuel, during a two-week road trip I recently took to the Great Lakes. I plan to give him these postcards, along with others from future trips, when he's older in hopes that they will inspire him to chase his own dreams, whatever those might be.

False Summit

It’s 12:00 p.m. on Sunday, July 30, 2023, and I’m lounging at the beach enjoying the white sands and green waters of Florida’s Emerald Coast. Today is my 40th birthday and a relaxing getaway is exactly what I needed after a two-week road trip out west, where I hiked the highest peaks of Colorado and Arizona. The reasoning behind my latest excursion was simple: if I’m going to be “over the hill,” then I might as well be standing on top of a mountain.